Survivorship Care

Survivorship Care

Definition and Scope of Survivorship

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), a “survivor” is defined as anyone with cancer, from the time of diagnosis through the remainder of life.¹ The Institute of Medicine, now the National Academy of Medicine, further described survivorship as encompassing comprehensive care after diagnosis, including prevention of recurrent and new cancers, surveillance, intervention for physical and psychosocial consequences of cancer and treatment, and coordination of care among providers.² As of 2022, there were an estimated 18.1 million cancer survivors in the United States, with that number expected to exceed 26 million by 2040.3

Survivorship Care Models and Standards

Various models have been proposed to address the full spectrum of care for the growing population of cancer survivors, including those from the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer, the American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Oncology Practice Initiative, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid, among others. However, these models had limitations in addressing the broad scope of cancer survivorship care.2,4,5

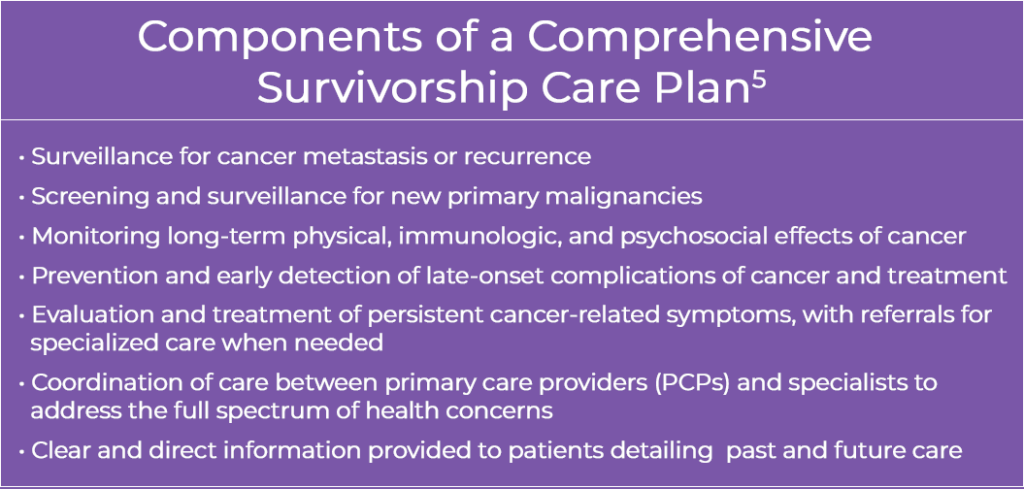

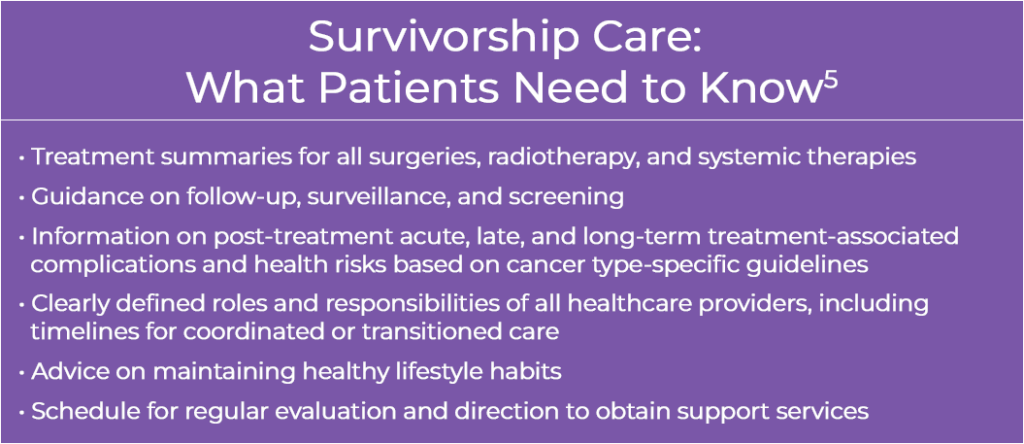

According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines for Survivorship, cancer survivorship plans should include the components below:5

A recently developed framework by Larissa Nekhlyudov, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, provides a foundation for systematic delivery of survivorship care in the United States. This model outlines the essential components of comprehensive care to address the complex issues affecting cancer survivors and is intended to inform the development of quality metrics to guide continuous evaluation and improvement. 2,4

Symptom Management

A key component of survivorship care is symptom control and minimizing toxicities associated with treatment. Inadequate symptom control diminishes quality of life, increases utilization of costly emergency and hospital care, and dissuades patients from pursuing life-prolonging therapies. Suboptimal management of treatment-related side effects and postoperative symptoms can prolong recovery time, increase patient distress, and interfere with overall disease management. Thus, improving symptom management is crucial in improving patient outcomes in survivorship care.

Efforts to implement digital health technologies to improve symptom management and symptom reporting by patients through the NCIs IMPACT (Improving the Management of symPtoms during And following Cancer Treatment) consortium have shown preliminary promise.6 For example, SIMPRO (Symptom Management Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Oncology), a multidisciplinary electronic symptom management program integrated with EPIC’s electronic health records (EHR) system has shown increasing use, with 48% of patients having used the tool at least once to report symptoms (16% were severe) as part of a research consortium across six health systems, involving >25,000 patients treated among 50 clinics.6,7 Despite technological and implementation challenges, EHR-integrated tools like SIMPRO show potential to decrease debilitating side effects of treatment, reduce acute care utilization, and improve survivor quality of life.6,7

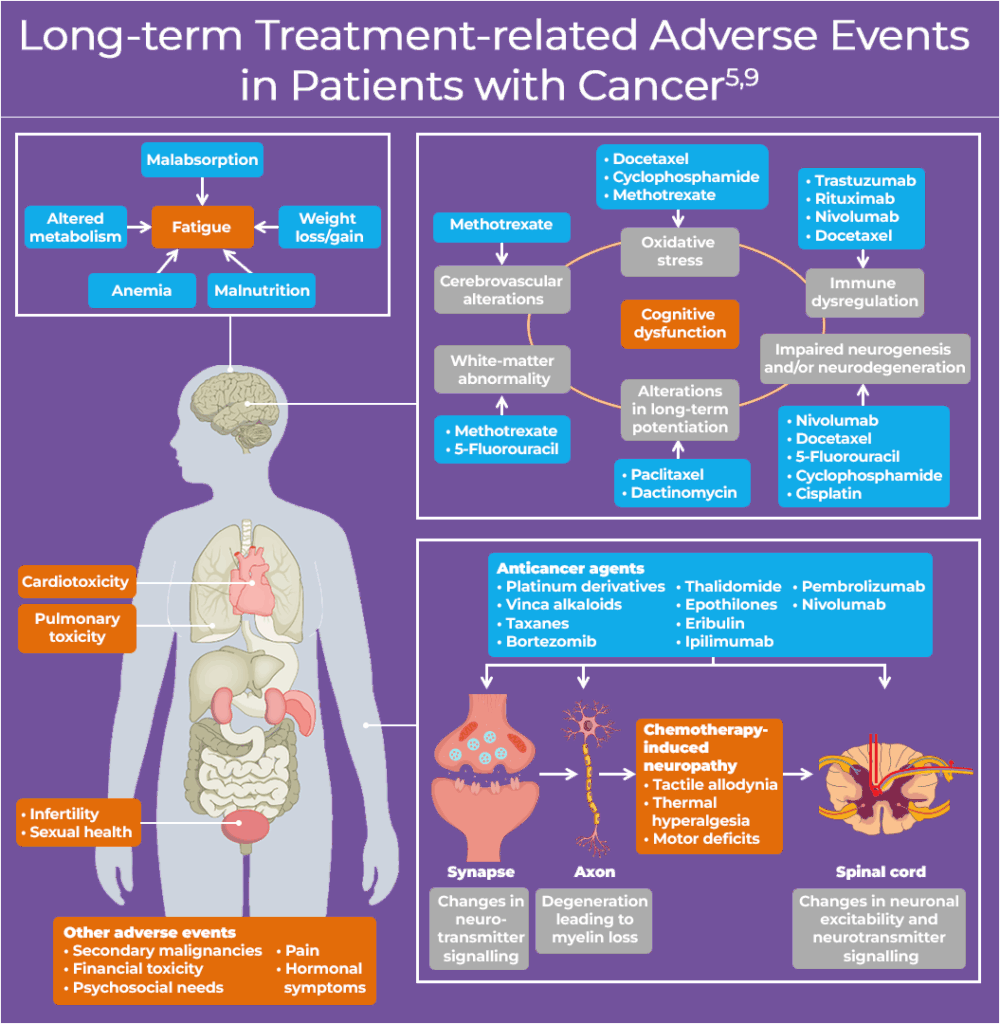

Long-Term and Late Effects

Many cancer survivors experience physical and/or psychosocial effects as sequelae from cancer and cancer treatment. Beyond acute symptoms, clinicians should also monitor and address long-term and delayed complications that may emerge months or years after treatment. Long-term and late effects can range from mild to severe, or even debilitating or life-threatening, leading to progressive or permanent disability.5 At least 50% of cancer survivors experience one or more long-term effects of treatment, including physical, psychosocial, cognitive and sexual abnormalities, as well as anxiety about recurrence and second malignancies. Survivors most commonly experience fatigue, pain, and depression.5,8,9 Late effects, such as cardiotoxicity can emerge, particularly in patients treated with anthracyclines or HER2-targeted therapies for advanced breast cancer.10

The exact prevalence of disease- and treatment-related sequelae is difficult to determine due to a lack of longitudinal studies comparing patients with and without malignancy. Incidence of late-onset effects have likely increased substantially with the use of increasingly complex, dose-intensive regimens—including combination regimens and novel agents. The diagram below depicts the multitude of long-term effects associated with oncologic therapies.

Multidisciplinary Coordination of Survivorship Care

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) Commission on Cancer recommend that all survivors receive a written survivorship care plan. These documents should address both clinical and personal needs, undergo regular review, and include a treatment summary, follow-up schedule, information on potential late effects, and lifestyle recommendations.11,12 Continuity and coordination of care, along with integration of multidisciplinary health services, are essential throughout survivorship to ensure individualized, high-quality care for every patient.12

Survivorship guidelines recommend disease-specific surveillance strategies based on cancer type, stage, and treatment. For example, the NCCN recommends periodic imaging and CEA monitoring for colorectal cancer survivors, while breast cancer survivors require annual mammography.5 Coordination of surveillance is often managed by oncologists initially but should eventually transition to primary care.11 Since many cancer survivors continue their care within primary care settings, effective communication between oncology, primary care teams, and other specialists is essential. Strong collaboration at this intersection can help ensure survivors experience the continuity of care they require.

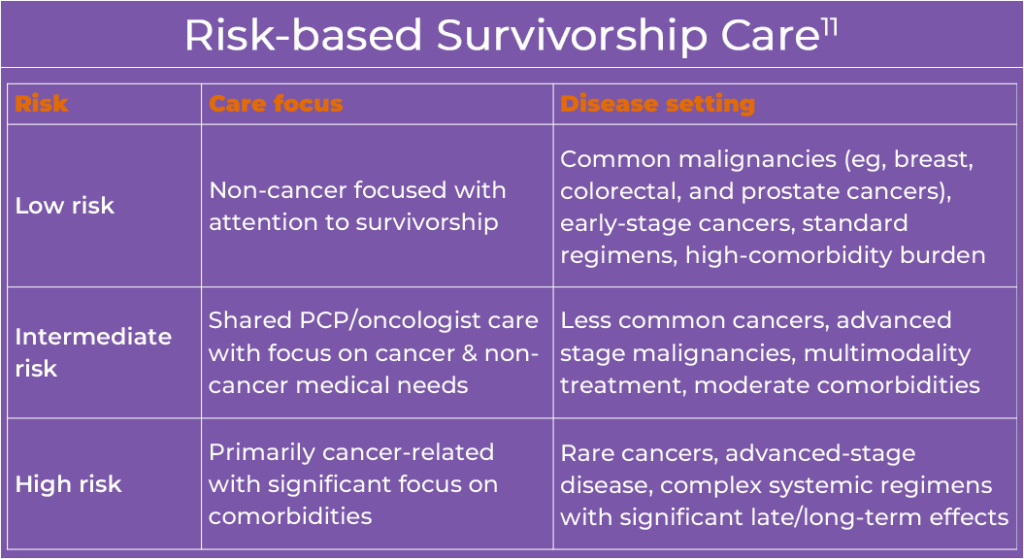

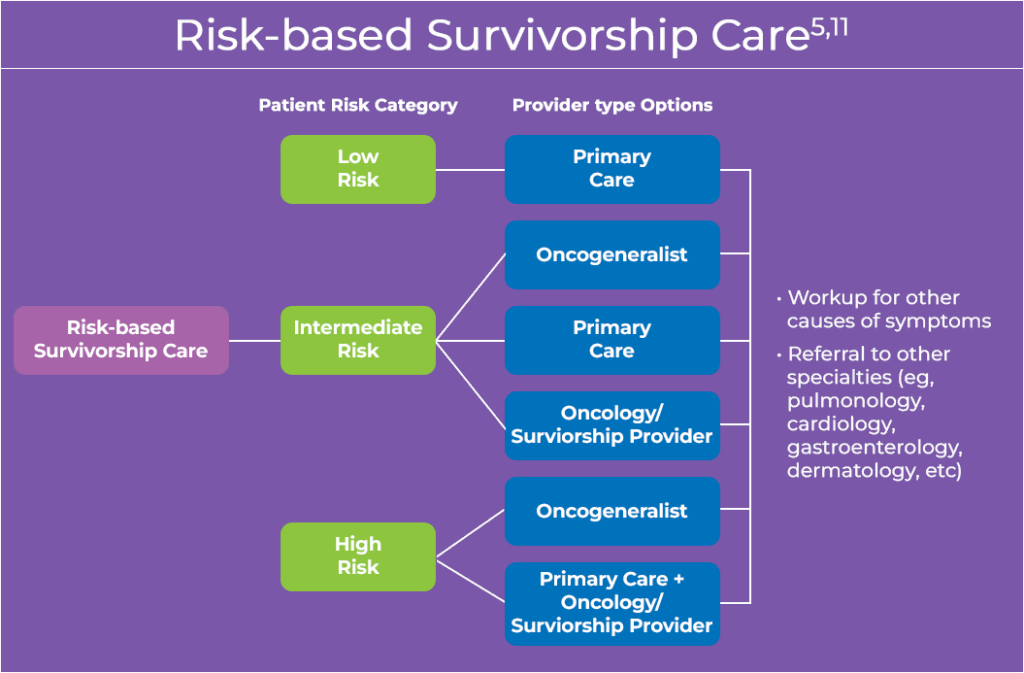

Developing an effective survivorship care plan begins with risk stratification to determine the intensity and setting of follow-up care. Patients at higher risk—such as those treated with complex regimens (eg, hematopoietic stem cell transplant), rare cancers of adulthood or childhood, or existing/potential late effects—may benefit from care in dedicated survivorship clinics staffed by oncology providers or oncogeneralists (PCPs specializing in survivorship care). These providers are uniquely positioned to balance cancer-specific follow-up with management of comorbid conditions and overall health maintenance.11

Regardless of risk level, all survivors should have a PCP for non-cancer–related care and prevention. For shared care models to be effective, clear and proactive communication between oncology and primary care teams is essential. Survivorship care plans should be developed early by the oncology team and revisited regularly until full transition to a PCP is appropriate. Various communication methods (ie, electronic health records, secure email, survivorship plans, and virtual/in-person consultations) can support continuity, reduce duplication, and improve outcomes across the care continuum.11 The figure below provides a framework for risk-based transition of survivorship care to primary care when apropriate.11

- Example based on 5 years post-initial treatment; transition of care may vary

An oncogeneralist is a primary care physician with specific training or experience in survivorship care

As part of the transition process, nurses and lay patient navigators play a crucial role within the care team by coordinating care among services and specialists, evaluating the medical, psychological, and practical needs of each patient; addressing challenges to care; and providing patient education. Patient navigators not only coordinate appropriate referrals, connect patients with resources, and advocate for individualized patient goals among the care team, but may be involved in facilitating assessment of side effects, emotional or spiritual distress, transportation needs, and insurance/finances, which often continue beyond the active treatment phase of cancer care.13

Health Promotion and Lifestyle

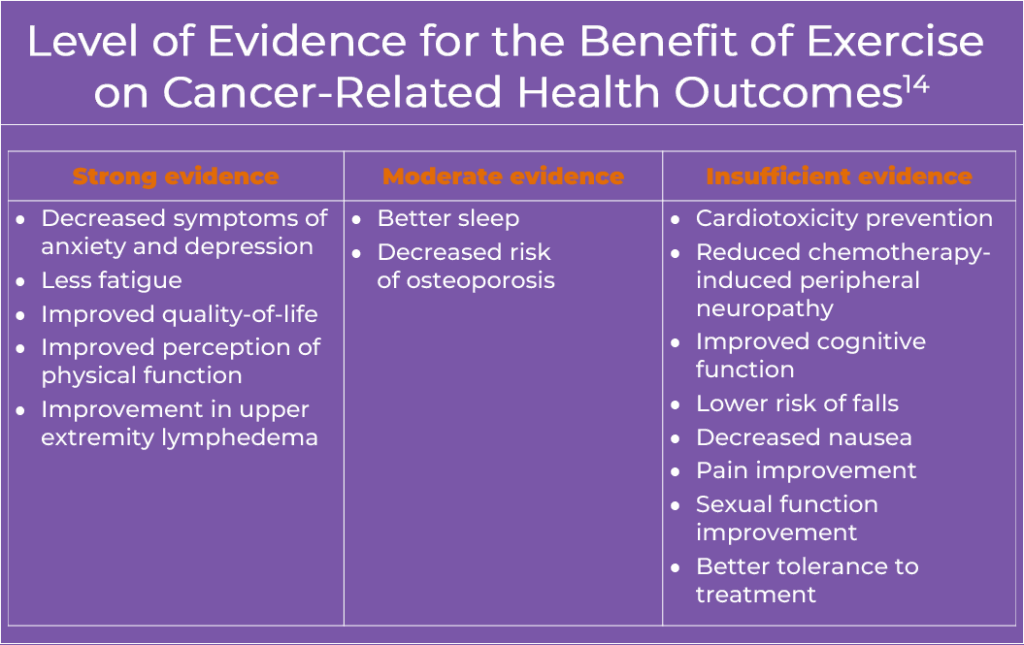

Healthy behaviors, such as smoking cessation, physical activity, and weight management are critical components of survivorship care.14 Furthermore, evidence suggests that exercise may improve fatigue, quality of life, and disease-free survival in several tumor types.15

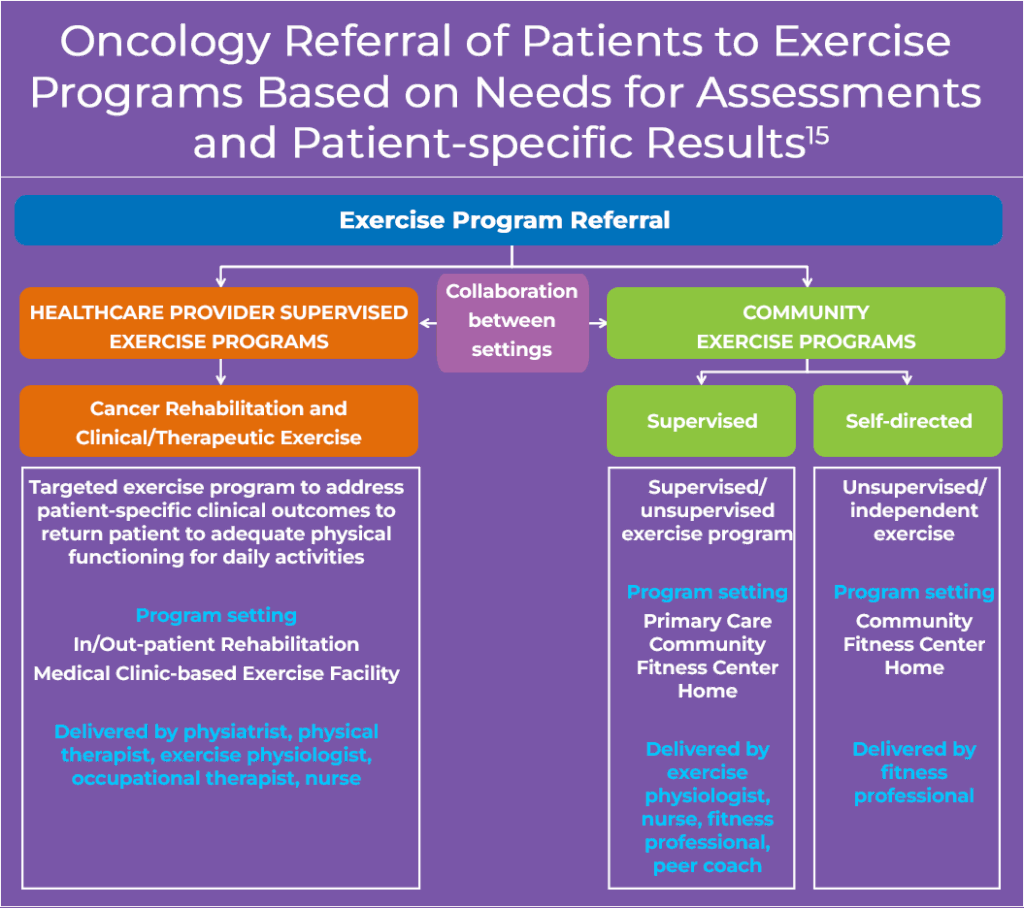

The growing research on exercise in cancer care highlights the need for clear guidance to help oncology clinicians support patients’ physical and emotional well-being from diagnosis through survivorship.1 The illustration below highlights a potential framework for exercise programming during and after treatment, including HCP-supervised exercise programs (inpatient or outpatient, public or private) and community/home-based programs. Given the aims of supporting patients physically and psychologically throughout the cancer journey and their survival, they may be referred more than once and in various settings based on their medical complexity and ability to self-manage their condition.15

For additional information, please visit the Survivorship Resources for Clinicians section at Additional Resources for Oncology Providers

References

- National Cancer Institute Office of Cancer Survivorship. Definitions. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/definitions

- National Cancer Institute. Office of Cancer Survivorship. Models of Survivorship Care. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/special-focus-areas/models-of-survivorship-care

- National Cancer Institute Office of Cancer Survivorship. Statistics and Graphs. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/statistics

- Nekhlyudov L, Mollica MA, Jacobson PB, et al. Models of cancer survivorship care: Current approaches and opportunities for improvement. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:362-370.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network®. Survivorship. Version 2.2025. May 23, 2025. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=3&id=1466

- Hassett MJ, Cronin C, Tsou TC, et al. eSyM: An electronic health record-integrated patient-reported outcomes-based cancer symptom management program used by six diverse health systems. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2022;6:e2100137. doi:10.1200/CCI.21.00137

- Cronin C, Barrett F, Dias S, et al. Electronic patient-reported outcomes in oncology: Lessons from six cancer centers. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2024;5. doi:10.1056/CAT.23.0331

- Valdivieso M, Kujawa AM, Jones T, Baker LH. Cancer survivors in the United States: A review of the literature and a call to action. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:163-173. doi:10.7150/ijms.3827

- Lustberg MB, Kuderer NM, Desai A, et al. Mitigating long-term and delayed adverse events associated with cancer treatment: Implications for survivorship. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:527-542. doi:10.1038/s41571-023-00776-9

- Armenian SH, et al. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: ASCO clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:893-911. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400

- Nekhlyudov L, O’Malley DM, Hudson SV, et al. Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: Gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e30-e38. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30570-8

- Hart NH, Nekhlyudov L, Smith TJ, et al. Survivorship care for people affected by advanced or metastatic cancer: MASCC-ASCO standards and practice recommendations. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32:313. doi:10.1007/s00520-024-08465-8

- Journal of Oncology Navigation & Survivorship. Transition to Survivorship. https://jons-online.com/issues/2018/july-2018-vol-9-no-7/transition-to-survivorship

- Rock CL, Thompson CA, Sullivan KR, et al. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:230-262. doi:10.3322/caac.21719

- Schmitz KH, Campbell AM, Stuiver MM, et al. Exercise is medicine in oncology: engaging clinicians to help patients move through cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:468-484. doi:10.3322/caac.21579

ALL URLs accessed October 28, 2025